BLACK MADONNA CATALOG

To make an appointment to view the exhibition please scroll down

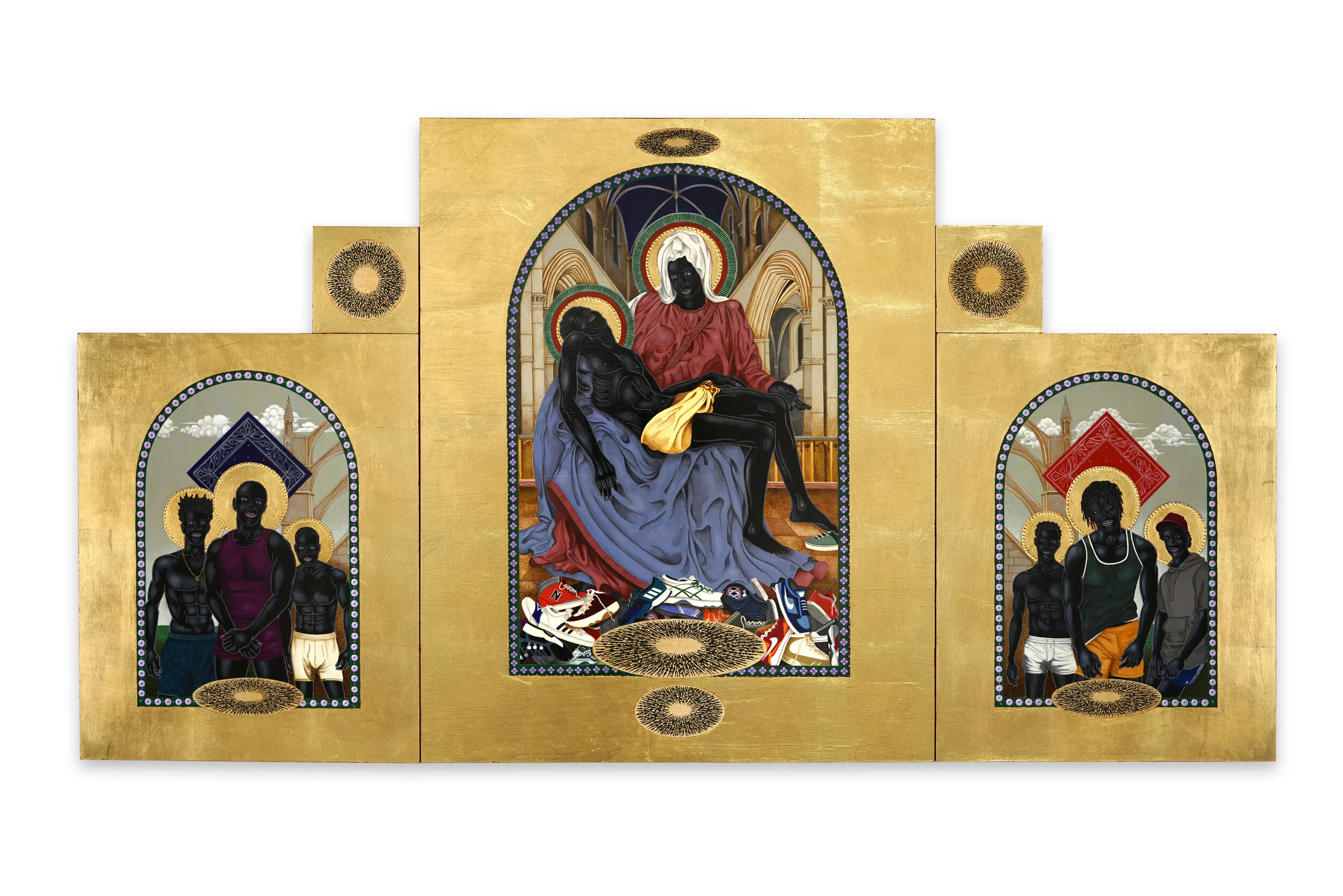

BLACK MADONNA

MARK STEVEN GREENFIELD

"For the faithful, the Black Madonnas represent the basis of theological mystery from which all possibility emanates. For the clergy, they provide cover for some unexplained religious dogma. For me, they held all the intrigue of confronting a blank canvas.” — Mark Steven Greenfield

William Turner Gallery is pleased to present, Black Madonna, an exhibition of new and recent work by Mark Steven Greenfield. The exhibition explores aspects of the African American experience in American culture, often critiquing and offering unique perspectives on a society still grappling with the consequences of slavery and racial injustice. As Greenfield has stated, “My work incorporates irony, humor, tragedy, pathos, history, and a myriad of other tools, to challenge long-held notions of race in a different way."

The exhibition highlights a striking new series of 17 Black Madonna paintings, which re-imagine these unique religious icons, that began appearing in the 13th and 14th centuries in churches throughout Medieval Europe. The origin and purpose of the Black Madonnas in religious iconography are somewhat of a mystery and the subject of much scholarly debate, which inspired Greenfield to infuse them with his own contemporary meaning and perspective.

Greenfield's versions are rendered in the Byzantine style of their art historical predecessors, with the black Virgin Mother and Baby Jesus as the central focus within circular compositions, or tondos. These tondos float amongst abstract discs, set within fields of lustrous, gold leaf. The Madonnas predominate before a variety of backgrounds, which were traditionally innocuous. Greenfield, however, presents these backdrops as various revenge fantasies, where white supremacists are cast in the role of victims, suffering the fates they often inflicted.

The effect is striking, the meaning unexpected. For Greenfield, a dedicated meditator, the discs symbolize the mantras one repeats during meditation, and often appear in his work. The Black Madonnas, seated innocently before the violence playing out behind, are the thoughts which come unbidden during meditation between mantras - to be acknowledged, then released. The Madonnas play their traditional role, conveying notions of maternal love, seemingly oblivious to these various scenes of retribution, where the rope is decidedly on the other neck.

Burnin’ Down the House, 2019, Acrylic and Gold Leaf on Wood Panel, 24 X 18 ”

Yet these role reversals are less about revenge fantasies and more about creating contexts for shifts in perspective - for empathy. Tinged with humor, titles like, Mississippi Cookout, and Burnin’ Down the House, invite us to imagine an alternate reality, so that we might better understand the brutal realities of the past as we navigate our way forward. As Greenfield states, “Fear of the “other” often devolves into mindless hatred. Yet, sometimes the path to empathy lies in the visualization of one’s physical victimization—particularly when paired with a symbol that has come to be associated with universal love.” He adds, “The revenge fantasy exists in the darker regions of the subconscious in response to centuries of injustice. It is subdued by the higher aspiration that leads toward a more saintly life. As during the Renaissance, when Black Madonnas first gained prominence, they serve as metaphors for a spectrum of new beginnings.”

Throughout his career, Greenfield's work has dealt with elucidating the African American experience - examining stereotypes and other acts of oppression, often by illuminating the most oppressive of acts - those of omission. Pieces like Escrava Anastacia , and Zong , are among a number of new works in the exhibition that present us with powerful images of figures and events neglected by history. Greenfield's images of a muzzled Anastacia, a legendary South American slave, known for her exceptional beauty and miraculous powers of healing, and the ill-fated souls cast to oblivion from the slave ship Zong, compel us to learn their stories.

This exhibition was a year and a half in the planning, yet feels uncannily destined for this moment. It opens at a time of unprecedented upheaval, where a global pandemic and outrage over continuing racial inequality, have challenged our institutions, and our perceptions of them, to the core. With Black Madonna , Mark Steven Greenfield brings an important and timely perspective to the discussion.

We look forward to welcoming you to view the exhibition virtually and by appointment, abiding by all of the CDC-recommended precautions.

Zong, 2019, Ink and Acrylic on Duralar.

Zong

On November 29, 1781 the crew of the slave ship Zong threw more than 130 slaves overboard because they had not stored enough food and water to sustain the "cargo" during the middle passage. Upon landing in Jamaica, they tried to file an insurance claim for the loss which was denied. The resulting 1783 court case, Gregson vs. Gilbert, held that under some circumstances the deliberate killing of slaves was legal. New evidence was introduced that found that the captain and crew were at fault due to a navigational error which prolonged the voyage. The Zong Massacre received increased attention on the testimony of a freed slave, Olaudah Equiano, giving rise to the abolitionist movement of the 18th century, and the end of British participation in the African Slave trade in 1807. The painting “The Slave Ship” 1840, by J.M.W. Turner was inspired by the event.

Escrava Anastacia , 2020, Acrylic and Gold Leaf on Wood, 16 x 16”.

Escrava Anastacia

A great deal of mystery surrounds Anastacia’s origins. Some claim she was born of royal lineage in Africa, while others suggest she was born in Brazil. All accounts agree that she was a slave of exceptional beauty with arresting blue eyes. She was purported to have possessed remarkable healing abilities and a number of miracles are attributed to her. She was very cruelly treated by her masters and was made to wear a muzzle-like facemask and heavy iron collar. The reasons for this punishment vary from trying to incite other slaves escape, to the claim that she resisted rape by her master, to a mistress jealous of her beauty. After a prolonged period of suffering she died of tetanus brought on by the slave collar. It is claimed that she healed the son of the master and mistress and forgave them as she died. There have been repeated attempts to have her canonized as a saint, but the Catholic Church refuses to acknowledge her existence, and has had her image removed from all church properties in Brazil. Nonetheless Anastacia has many devoted followers among the poor and disenfranchised, and shrines to her can be found throughout the country.

Mark Steven Greenfield

Mark Steven Greenfield is a native Angelino, and son of a Tuskegee Airman, which led to spending the first part of his life abroad, living on military bases from Taiwan to Germany, until returning to LA at the age of ten. In high school Greenfield studied with revered Los Angeles artist, John T Riddle. Riddle quickly noted Greenfield’s talent, but saw that he was vulnerable to the influences and dangers confronting black youth at the time. Riddle remarked, "You could be a pretty good artist....if you live that long.” This got Greenfield’s attention and set him on the path that would define the course of his life.

Greenfield went on to study with Charles White, at Otis Art Institute, and received his Bachelor’s degree in Art Education in 1973 from California State University, Long Beach and a Masters of Fine Arts degree in painting and drawing from California State University Los Angeles in 1987. Greenfield’s work has been exhibited extensively throughout the United States most notably with a comprehensive survey exhibition at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles in 2014, and in 2002 at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia. Internationally, he has exhibited at the Chiang Mai Art Museum in Thailand; at Art 1307 in Naples, Italy; the Blue Roof Museum in Chengdu, China; 1333 Arts, Tokyo, Japan; and the Gang Dong Art Center in Seoul, South Korea.

Greenfield is a recipient of the L.A. Artcore Crystal Award (2006) Los Angeles Artist Laboratory Fellowship Grant (2011), the City of Los Angeles Individual Artist Fellowship (COLA 2012), The California Community Foundation Artist Fellowship (2012), the Instituto Sacatar Artist Residency Fellowship in Salvador, Brazil (2013) and the McColl Center for Art + Innovation Residency in Charlotte, North Carolina (2016). He was a visiting professor at the California Institute of the Arts in 2013 and California State University Los Angeles in 2016.

From 1993-2011, Greenfield worked for the Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs as director of the Watts Towers Arts Center, and later as director of the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, Barnsdall Park. He has served on the boards of the Downtown Artists Development Association, the Armory Center for the Arts, the Black Creative Professionals Association, the Watts Village Theatre Company and was past president of the Los Angeles Art Association/Gallery 825. He currently teaches drawing and design at Los Angeles City College, and serves on the board of Side Street Projects.